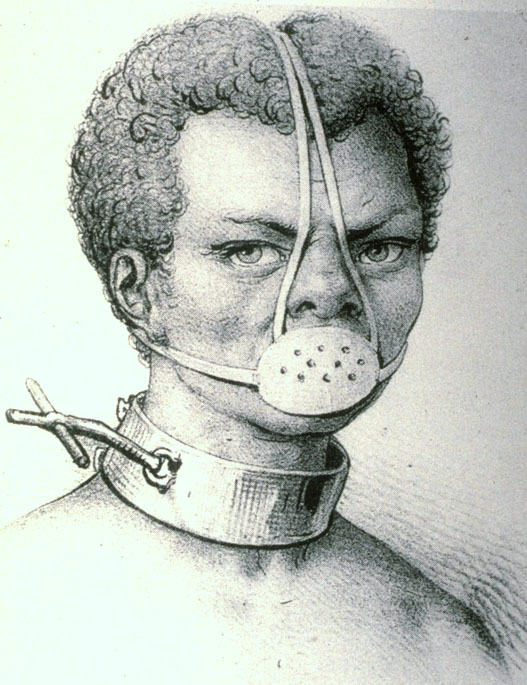

"Caption "Esclave Marron a Rio de Janeiro" (Fugitive/Runaway Slave in Rio de Janeiro), based on a drawing by a Mister Bellel. The engraving illustrates a brief article on fugitive slaves in Brazil, and is apparently derived from first-hand information. "Captured fugitives," the article notes, "are forced to do the hardest and roughest work. They are ordinarily placed in chains and are led in groups through the city's neighborhoods where they carry loads or sweep refuse in the streets. This type of slave is so frightful that, while they have lost all hope of fleeing again, they think of nothing but suicide. They poison themselves by drinking at one swallow a large quantity of strong liquor, or choke/suffocate themselves by eating dirt/earth. In order to deprive them of this way of causing their own deaths, they put a tin mask on their faces; the mask has only a very narrow slit in front of the mouth and a few little holes under the nose so they can breathe" (p. 229; our translation)."

Image and text found on US Slave Blog. Link here.What is that thing in 12 Years a Slave?

From the scene on the boat in "12 Years a Slave"

From the scene on the boat in "12 Years a Slave"

September 14, 2015

By Toussaint Heywood

In the movie 12 Years a Slave, a man is shown with a tin mask chained over his mouth, on the ship taking Solomon Northup and others from Richmond to New Orleans to be sold.

Northup does not mention anything similar in the book. The mask is presumably based on a famous lithograph published in 1839.

The problem is that this form of punishment was rarely, if ever, used in the U.S. The man in the lithograph below is a Brazilian drawn by Jacques Arago early in the 19th Century, though the drawing has been widely copied and sometimes adapted to portray a woman.

Iron mask and collar for punishing slaves, Brazil, 1817-1818 Source.

Iron mask and collar for punishing slaves, Brazil, 1817-1818 Source.

Even the supposed purpose of the mask doesn't fit with North American slavery. It was to prevent the wearer from committing suicide by eating dirt or, less often, by drinking alcohol.

This was a complaint not typical in Virginia where the slaves in 12 Years embarked, and certainly not on shipboard. Clay-eating was recognized in the deep south among both blacks and whites as an odd but not lethal habit.

Sir Charles Lyell wrote on a visit to the U.S. deep south, "We observed several negroes there, whose health had been impaired by dirt-eating, or the practice of devouring aluminous earth,—a diseased appetite, which, as I afterwards found, prevails in several parts of Alabama, where they eat clay." He doubted it was due to lack of food because he "was told of a young lady in good circumstances, who had never been stinted of her food, yet who could not be broken of eating clay."

That does not mean a gag was never used to punish slaves here. The U.S. gag or bit or muzzle was meant to punish slaves by preventing them from talking or eating anything without it being removed, though it did not cover the face.

A journeyman cabinet-maker from the north reported: "In September, 1837, at 'Milligan's Bend,' in the Mississippi river, I saw a negro with an iron band around his head, locked behind with a pad lock. In the front, where it passed the mouth, there was a projection inward of an inch and a half, which entered the mouth. The overseer told me, he was so addicted to running away, it did not do any good to whip him for it. He said he kept this gag constantly on him, and intended to do so as long as he was on the plantation: so that, if he ran away, he could not eat, and would starve to death. The slave asked for drink in my presence; and the overseer made him lie down on his back, and turned water on his face two or three feet high, in order to torment him, as he could not swallow a drop.--The slave then asked permission to go to the river; which being granted, he thrust his face and head entirely under the water, that being the only way he could drink with his gag on. The gag was taken off when he took his food, and then replaced afterwards."

Decades later, Milliken's (Milligan's) Bend would become the site of a June 7, 1863 battle, one of the first where soldiers of "African descent" fought. Charles A. Dana later recalled, "The bravery of the blacks in the battle at Milliken's Bend completely revolutionized the sentiment of the army with regard to the employment of negro troops."

Other U.S. witnesses described similar items. C. G. Parsonswrote in 1855: "The Gag is a piece of iron, about three inches in length, one inch in width at one end, half an inch at the other, and about one eighth of an inch in thickness. This instrument is put into the mouth, over the tongue, with the narrow end inside, while the wide end is left projecting through the lips. The outer end is inserted into a small strap of iron that passes over the mouth, the ends of which extend around to the back of the neck, where they are fastened together by a rivet, or a padlock. With this long, wide piece of iron thus confined on the tongue, the slave is truly gagged, — as he is unable to utter a syllable."

A Civil War officer observed near New Orleans: "Another article is a heavy iron collar, with a mouth-piece, or 'gag' attached. This gag comes up from beneath the chin, and is immovably fixed in the mouth. In order to speak, eat or drink, it must be removed."

While the producers of 12 Years a Slave may have wanted to show the torture inflicted on enslaved people by metal instruments, they chose an uncommon Brazilian devise that was actually milder than what could have been used in the U.S.

One of the best analyses of the lithograph showing the Brazilian slave is by J. Handler and A. Steiner, "Identifying Pictorial Images of Atlantic Slavery: Three Case Studies," Slavery and Abolition 27 (2006), 56-62. The original image appeared in Jacques Etienne Victor Arago, Souvenirs d'un aveugle, Voyage autour du monde par M. J. Arago, (Paris, 1839-40), vol. 1, facing p. 119.

Source link here.

No comments:

Post a Comment